An Explanation of Roulette

Derived from the French for “little wheel,” Roulette has players choose single numbers, groups of numbers, or colors to place bets on. Once bets have been placed, a croupier (dealer) spins the wheel in one direction, and spins a ball in the opposite direction on the track running on the outer edge of the wheel. Eventually the ball loses momentum, falling onto the wheel of one of the 38 colored and numbered pockets. Edward O. Thorp and Shannon felt they could predict where the ball would end up because casinos allowed players to bet for a few seconds while the ball was spinning. This gave them the necessary time to track the ball’s momentum.

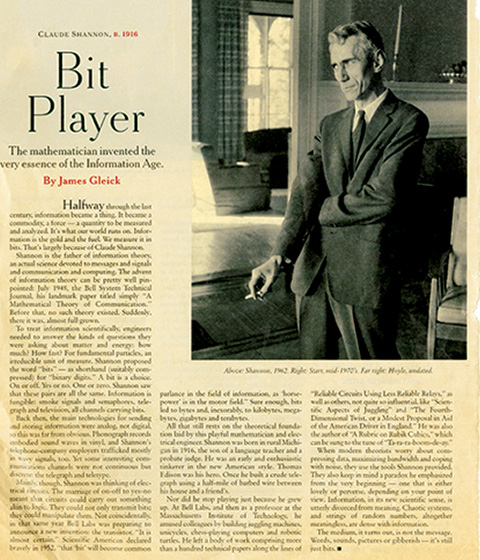

“The Lives They Lived: Claude Shannon, B. 1916, Bit Player”

Claude Shannon (1916–2001) was an American mathematician, electrical engineer, computer scientist, and cryptographer known as “the father of information theory.” Shannon’s theories laid the groundwork for the electronic communications network now used all over the planet. Shannon and Edward O. Thorp met in September 1960 at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and applied mathematics to see if they could predict where the ball would land on a roulette wheel.

Thorp originally became intrigued about the roulette wheel while in high school studying planetary positions. He felt there was an analogy between the circling roulette ball and an orbiting planet, or of a pendulum that is gradually dissipating energy. “Since planetary positions were accurately predictable, I thought I might be able to forecast the outcome of a roulette pin.”

— Edward O. Thorp. A Man for All Markets: From Las Vegas to Wall Street, How I Beat the Dealer and the Market. Random House Publishing Group, 2017. Page 44.

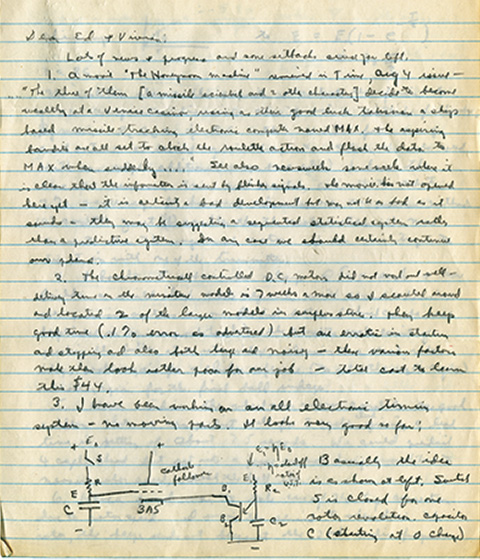

August 6, 1961. Articles from the UC Irvine Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Edward O. Thorp Papers.

Letter from Claude Shannon to Edward O. Thorp about the Wearable computer

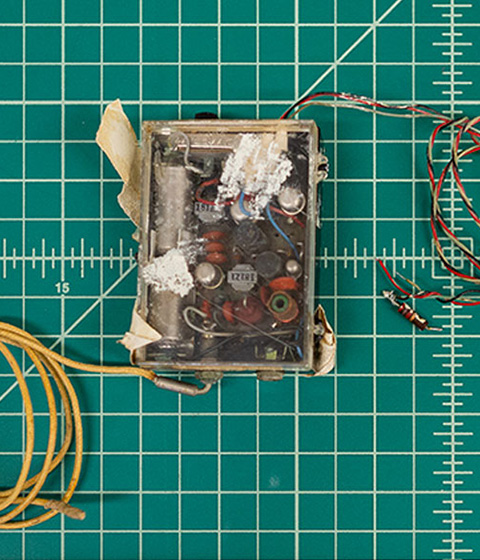

Wearable Computer

“The computer has 12 transistors that allowed its wearer to time the revolutions of the ball on a roulette wheel and determine where it would end up. Wires led down from the computer to switches in the toes of each shoe, which let the wearer covertly start timing the ball as it passed a reference mark. Another set of wires led up to an earpiece that provided audible output in the form of musical cues — eight different tones represented octants on the roulette wheel. When everything was in sync, the last tone heard indicated where the person at the table should place their bet.”

— Billy Steele. Engadget.com. The Unlikely Father of the Wearable Computing. Distro. September 13, 2013.

Using the model, they were able to predict any single number with a standard deviation of 10 pockets. This converts to a 44% edge on a bet on a single number. Betting on a specific octant gave them a 43% advantage. Thorp and Shannon went to Las Vegas in August 1961 to test the computer in a real environment. It was successful “turning small piles of dime chips into large ones.” The difficulty they encountered had to do with output. While the small computer worn around the waist was inconspicuous enough, the earpiece proved more difficult.

“Even though they were steel, they were so fine that they broke frequently, leading to long interruptions while we returned to our rooms and went through the tedious process of doing the repairs and then rewiring [the bettor].” Between this and the knowledge that casinos could change the rules at any time to stop allowing betting after the ball was spun, they ended their project.

— Edward O. Thorp. A Man for All Markets: From Las Vegas to Wall Street, How I Beat the Dealer and the Market. Random House Publishing Group, 2017. Page 133.

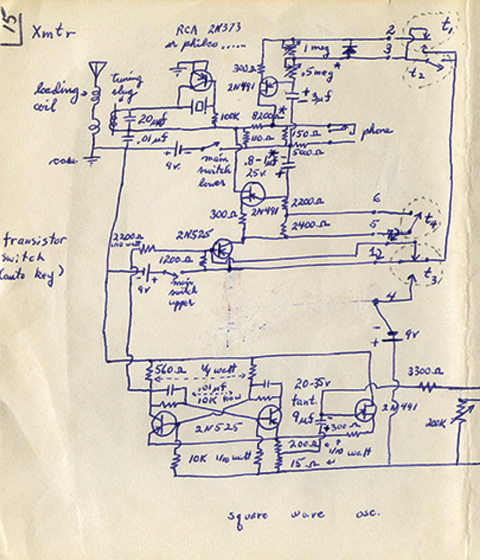

Electrical Diagram for Wearable Computer/Schematic of Roulette Wheel

“Well into one winning session, a lady next to me looked over in horror. Knowing I should leave, but not why, I raced to the restroom and there in the mirror saw the speaker peeking out from my ear canal like an alien insect.”

Edward O. Thorp. A Man for All Markets: From Las Vegas to Wall Street, How I Beat the Dealer and the Market. Random House Publishing Group, 2017. Page 133.

Man’s Shoe

Using the roulette computer was a two-person job. One person would wear the device and time the wheel. Edward O. Thorp and Claude Shannon had trained their big toes to operate switches hidden in their shoes. The other person, the bettor, would sit at the table with a receiver (a tiny loudspeaker pushed into one ear canal and connected by very thin wires to the radio receiver, which was concealed under his clothing), hearing the results as various audio tones.

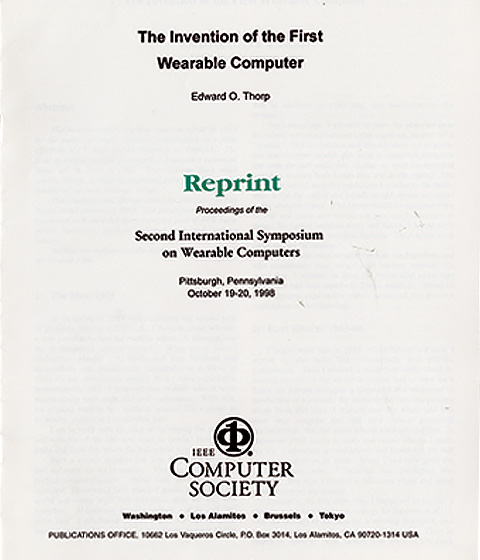

“The Invention of the First Wearable Computer.”

Edward O. Thorpe. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Wearable Computers. Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. October 19–20, 1998.

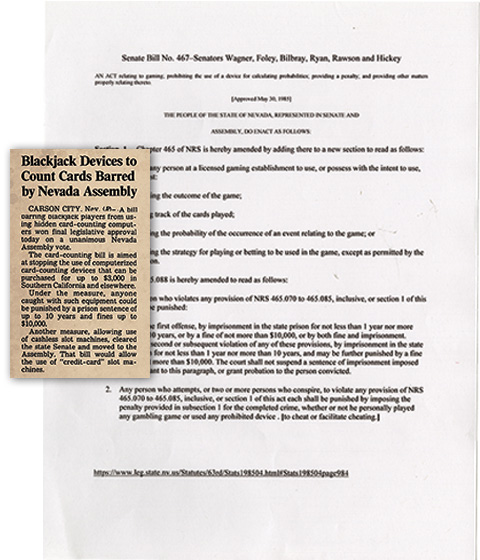

Wearable Computers Outlawed in Nevada on May 30, 1985

- Senate Bill Number 467. 1985 State Senate (Nevada, 1985).

- Blackjack Devices to Count Cards Barred by Nevada Assembly. Los Angeles Times. May 24, 1985.

In 1961 there were no laws in Nevada about the use of computers in casinos. Twenty-four years later Nevada passed an emergency measure banning use or possession of any device to predict outcomes, analyze probabilities, help with strategy, or count cards.

Postcard from The Mint Casino in Las Vegas, 1965

Picturing a Roulette Gaming Guide.

MIT Timeline

Edward O. Thorp and Claude Shannon reveal their invention of the first wearable computer, used to predict roulette wheel. The system was a cigarette-pack sized analog computer with 4 push buttons. A data-taker would use the buttons to indicate the speed of the roulette wheel, and the computer would then send tones via radio to a bettor’s hearing aid. Though the system was invented in 1961, it was first mentioned in Edward O. Thorp’s, Beat the Dealer (revised ed. 1966). The details of the system were later published in Review of the International Statistics Institute, Vol. 37, No. 3, 1969. Thorp also disclosed a similar system for beating the Wheel of Fortune gambling game in Life Magazine, March 27, 1964, Pages 80–91.

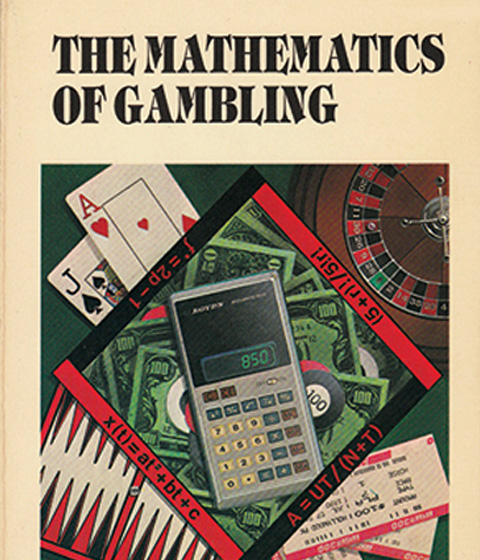

The Mathematics of Gambling

“More than twenty years after the publication of Beat the Dealer, the best-selling book on winning at blackjack, Dr. Edward O. Thorp again focused his attention on gambling games with an analysis of Baccarat, Backgammon, Blackjack, Roulette, and Wheel of Fortune. In easy-to-understand language, learn what a leading mathematician discovered in thirty years of computer-assisted research. This is the long-awaited publication to Dr. Thorp’s accumulated work on gambling.”

Back cover of the Mathematics of Gambling.

High/Low Strategy for One Deck

What to Count:

- Start with the count of 0.

- Add (+) 1 for the following cards: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

- Cards 7, 8, and 9 = 0.

- Subtract (–) 1 for 10, Jack, Queen, King, Ace.

- Explanation: When the count is high, the remaining deck is favorable to the player and you should bet more. When the count is low, the casino (house) benefits and you should bet low.

- Question: Given this scenario, would you bet more or less on your next hand?